Nova Scotia has long been a hotbed of folk art, a region where self-taught artists transform the ordinary into the extraordinary. Meanwhile, the broader world of Outsider Art has captivated collectors and institutions, championing artists who exist outside traditional fine art circles.

But where do we draw the line between folk, naïve, and outsider art? Are these distinct categories, or do they overlap more than we assume?

As Hilary Nangle describes in Making the Ordinary Extraordinary: Nova Scotia Folk Artists Add Pizzazz to Daily Life, folk art is deeply connected to community, function, and cultural heritage. Meanwhile, as theunintendedcurator argues in Outsider, Folk, or Naïve Art?, Outsider Art is often more personal, visionary, and psychologically driven.

Yet, as we’ll see, these categories are far from rigid. In fact, artists like Bradford Naugler, Barry Colpitts, and Jean-Michel Basquiat challenge these definitions, forcing us to reconsider how we talk about self-taught artists. At the same time, contemporary artists like Dana Hatchett, whose abstract faces have drawn comparisons to Picasso and Dubuffet, complicate the notion of who truly belongs in the Outsider Art category.

In Nova Scotia, folk art is a tangible reflection of its seafaring and farming culture. This is evident in the work of artists like:

Folk art, at its core, is an extension of its environment—it tells stories not just about the artist, but about the community from which it emerges. But what happens when an artist isn’t connected to a specific community or tradition?

Take Henry Darger, the Chicago janitor who secretly wrote a 15,000-page novel and painted hundreds of surreal watercolors, only discovered after his death. Or Judith Scott, who spent decades in an institution before developing her own fiber-wrapping sculpture technique.

As theunintendedcurator argues, Outsider Art has become a catch-all for artists outside formal training, even if some outsiders (like Basquiat) eventually gain mainstream success.

Many artists exist in both worlds, challenging our attempts to separate them:

The tension between folk and outsider art is that folk art is often framed as nostalgic and cheerful, while outsider art is seen as raw and psychological. Yet, many folk artists live on the fringes of society, and many outsider artists become part of the fine art world.

Even Basquiat, who began as a true outsider, was exhibiting alongside Warhol within a few years—was he still an outsider, or had the fine art world absorbed him?

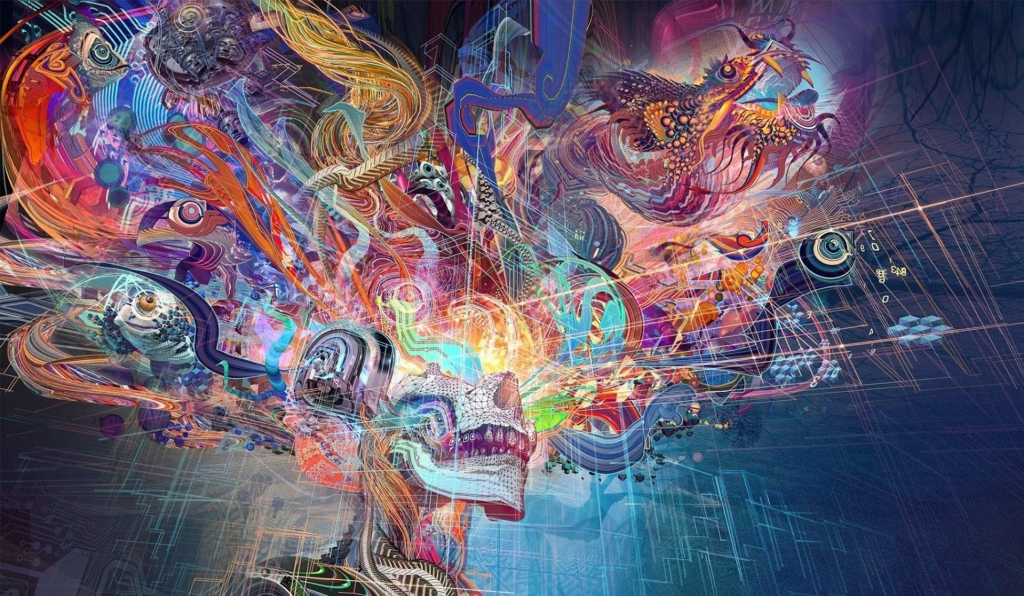

Unlike folk artists who work within a regional or cultural tradition, Dana Hatchett’s work is firmly rooted in the outsider aesthetic:

Hatchett’s work is a reminder that Outsider Art continues to evolve. While early outsider artists were often discovered posthumously, today’s outsiders—like Hatchett—can be actively collected, critiqued, and exhibited within their lifetime.

Labels like Folk Art and Outsider Art are not neutral—they are shaped by museums, collectors, and art historians.

As Hilary Nangle notes, collectors and institutions are drawn to the energy and authenticity of folk and outsider art, but they also reshape how it is valued and understood.

These shifting definitions raise a fundamental question: Are these labels helping to preserve these art forms, or are they tools used to control how artists are perceived and valued?

What remains true for both genres is their ability to speak directly to the viewer—to create work that is intuitive, deeply personal, and free from the constraints of formal artistic training.

At their core, folk and outsider artists are driven by an irrepressible need to create. Whether their work is defined as folk, outsider, naïve, or visionary, what matters is that it continues to be made, collected, and celebrated.

Established in 2025, Lunenburg YYZ Gallery represents artworks of established and emerging Atlantic Canadian artists.

Lunenburg YYZ Gallery is an online art gallery featuring a curated collection of unique and meaningful pieces. While the gallery operates online, the artwork is physically located in Toronto. Purchases can be made directly through the website, and in-person viewings can be arranged by contacting the gallery. Whether you’re looking to add to your collection or discover something new, we’re here to help you find the perfect piece.

Lunenburg YYZ Gallery Inc.

(416) 317-0389

www.lunenburgyyz.art

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

© Copyright 2025 Lunenburg YYZ Gallery Inc